Screen Share (Eliza's Version)

I'm remaking myself in Paris’s image. I fear that when I get home, no one will recognize me.

Hi, friends! I’m adding a new feature to Artichoke Heart this week. The magazine with which I did most of my writing in college decided to archive almost all of its online content, including all of my work. The stories are still available in their print layout on issuu.com, but I don’t think that makes for the most accessible reading experience. In the tradition of Taylor Alison Swift, I’m taking this opportunity to republish my past work here. You’ll receive “Eliza’s Versions” on Wednesdays as I work backward through previously published pieces. I hope you enjoy reading them for the first time or with fresh eyes, as I have.

It’s 4 a.m. in Paris, France. From deep in my fog of sleep and illness, I do some mental math. That makes it 9 p.m. in Houston, admittedly a more reasonable time to be blowing up someone’s phone. My screen lights up with the WhatsApp video call icon and my mother’s name. As quickly as the ringtone started pounding in my brain, it stops. Stutters. Then another call is coming through.

I’m awake now. My mom is trying to reach me in the middle of the night from a continent away. That can’t be good. I pick up, but neither the video nor the audio will connect. She texts me, “Please pick up.” Something must be wrong.

I’ve been in Paris for a little over two weeks now. I’ll be here for the next seven months, studying abroad and interning at an independent bookstore, though in January, I don’t know about that last part yet. I just know that I have a substantial scholarship to spend and a lifelong desire to live in Paris for as long as possible.

I also have Covid. I caught it just in time to miss my first week of classes at Sciences Po, the university at which I’ve enrolled here. I try to find meaning in this where there is none.

My symptoms are minimal. The worst of it is the quarantine in my tiny apartment, formerly a servant’s room on the seventh floor of a Haussmannian building in the center of the city. I have a glorious view of Notre Dame, but no air-conditioning or elevator. My lungs are tired enough that I don’t make the descent downstairs except to receive a DoorDash delivery of toilet paper and cheap wine, when I run out of both these essentials on day three of isolation.

There’s nowhere in the paltry 130 square feet to relax besides my bed, so that’s where I’ve been for the past five days. I’ve read a book each day for lack of Wi-Fi, and I’m nearly delirious with my longing for a negative test result.

Wi-Fi. My mind snaps back to alert. I don’t have Wi-Fi, and my service is spotty, and my mom is trying to reach me, and we can’t get through to each other. I text her, “I’m trying to call back, but you’re not answering.” Then I ask, “Is everything okay? It’s 4 a.m.”

She says she’s okay and that she knows what time it is. My anxiety switches quickly to annoyance. I fire off a snarky response, since I still can’t get a call to go through: “Did Hampton get into UT or something? That’s the only way this would make sense.”

A suspended moment before her response: “Then you should pick up.”

Paris is like a dream, like something I’ve gotten away with that could at any moment evaporate before me. I walk past Café de Flore and climb to the peak of Père Lachaise cemetery, reading at Hemingway’s haunts and retracing the steps of Balzac’s famous protagonist. Paris, à nous deux maintenant, and I’m ready. I waited my whole life.

Slaking my thirst with annual rewatches of Sabrina and Midnight in Paris, I’d come to think of the city as a way out, if only I could get there. In my taxi from the airport, I looked out at the Seine as it churned, brown and murky under a drizzling sky. I’m not one for superstition, but it felt like an inauspicious start; I couldn’t even see the Eiffel Tower through the fog.

In his collection The Art of Travel, contemporary philosopher Alain de Botton writes of the breach between the imagined and actual experience of travel, “where our appreciation of aesthetic elements remains at the mercy of perplexing physical and psychological demands.” It’s an entirely different endeavor to let movies or daydreams transport you than to confront your dreams in the form of a lonely city on a rainy day—or a positive Covid test.

It was still easier than I’d expected to leave my life behind. It took me until right before I left the country to find a solid community on campus, after a series of false-start friendships and too much time wasted trying to make myself into someone I’m not. Going to UT was always in anticipation of going abroad. I counted down the months until I could move away, and now that I’m here, the grandeur of the city throws into stark relief the paucity of my college experience.

If the world is my oyster, however, those long months in Austin made me a pearl. When I disconnect my American phone number, I don’t tell people. As soon as I’m hired for my summer internship, I drop my sorority. If I’m to prolong my time here, I’ll have other uses for my dues payments.

While my phone number is deactivated, however, I’ve never been more active on Instagram. At first I fear my oversharing is becoming obnoxious, but then I realize I could not care less. I finally unfollow so many people whom I know I won’t miss. I don’t have to worry about whether they’ll take offense because I’m 5,000 miles away. The distance can be isolating, but it is also liberating.

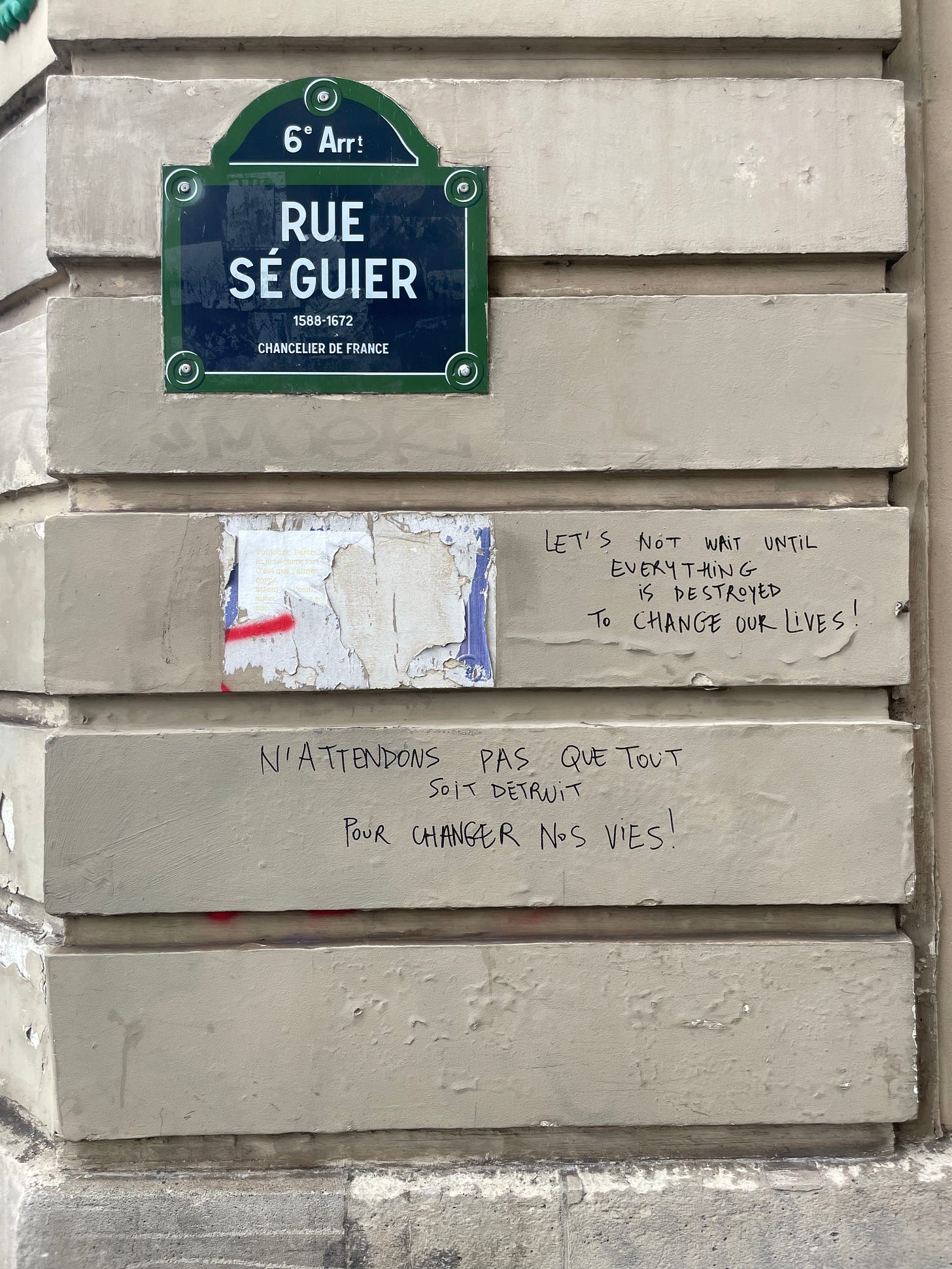

For every 10 pictures I post, I take a thousand more. Little things that I don’t want to forget: the way the dawn breaks over my window railing, blurry after stumbling home from the club at 5 a.m. The lipstick kisses covering Simone de Beauvoir’s grave. The chickpeas and leek rice bowl that my friend throws together at her apartment after spending our afternoon reading in the Jardin des Plantes. Graffiti on my street corner that reads “LET’S NOT WAIT UNTIL EVERYTHING IS DESTROYED TO CHANGE OUR LIVES!” Graffiti on a building across from my favorite restaurant that simply says “ABSURD.” Both are messages from the universe meant for me alone.

There are things, too, that pictures can’t capture, that won’t translate over FaceTime, that I know I’ll have to wait to explain in person. The dramas of my young adulthood play out against a backdrop of world history: There’s the Pont Neuf, the oldest bridge over the Seine, inaugurated in 1607. Standing on the southern end, you can just see a Scottish flag hanging above The Highlander pub, where my new friends and I convene at least once a week. This palimpsest of a city gives my movements a new significance.

When I think about how I’ll try to retell certain stories to my friends and family, it strikes me that all of this will soon be a memory. The separation between us will someday collapse, and with it, the distance between the girl I once was and the one I’ve discovered here. I struggle to synthesize these two selves. I’m remaking myself in Paris’s image, and I fear that when I get home, no one will recognize me.

My new reality—and identity—doesn’t translate all the way. The digital medium has a flattening effect that leaves me with a surfeit of experience. I still cry when I write home, willing the stamps to carry all my love across the ocean as I kiss them and slip them into the ubiquitous yellow mailboxes. Inevitably, I wish for something tangible in return. I count down the days until I can fly home for my brother’s high school graduation, then until my mom and stepdad come through the city on their honeymoon.

My friends text in our group chat about new traditions they’ve taken up since I’ve been gone, and my future roommates go house-hunting without me for where we’ll live together senior year. I know my absence makes things more difficult for them, and though they’re happy to do it, I feel like I should be there.

My brother gets into his dream school, and I can’t even figure out a way to pick up the phone.

Søren Kierkegaard, the prototypical Absurdist philosopher, wrote in his journals that “to act by virtue of the absurd, is to act upon faith” and in defiance of one’s rationality, where it would attempt to reason that action is impossible. In my isolation, I have faith that despite the changes at home that I’m missing, I am changing, too.

I don’t know how to explain the tension between my loneliness and my sense of belonging in this city without seeming unreasonable, ungrateful, or out of touch. But that’s how I feel—out of touch with reality. The graffiti echoes in my head: It’s not lost on me how absurd my life is right now.

It’s not often that a childhood dream comes true, or if it does, that it is so different than one imagined. Ever since my mom read me the Madeline picture books, I’ve held Paris in my mind as a home, a new place to be from. Now that I’m an adult, I feel a pressure towards independence. I catch the flu on a trip to Berlin, so I have to take myself to the emergency room and communicate my symptoms in what little I remember from my high school language unit on body parts. The nurses and I rely heavily on Google Translate, but they complement my accent nonetheless. People tell me that it’s like I’m living in a movie, and most of the time that rings true, but any film director worth their salt would reduce to a ridiculous montage the five hours in the hospital waiting room watching dubbed-over American flicks.

This is not a dream or a rom-com or an extended vacation; it’s real life. But I struggle to stay grounded in reality when it can resemble all three. The word “struggle” sounds like it could be a portmanteau of “straddle” and “juggle,” and I imagine myself with my legs stretched between two tight ropes while I try to keep bowling pins twirling through the air. Most days, living in Paris feels like doing double-time at the circus.

There is one particularly strange part of living so far from everyone and everything I know and love, perhaps the part that I find most difficult to describe: Any new friend I make here will never fully understand the context I’ve brought with me. I am my mother’s daughter, but they will never meet her.

In a way, my study abroad friends become my own little family, albeit one that has an expiration date. I travel with them, like an adoptee. When I join their university’s cohort for a day trip to Giverny, their program coordinator asks which student brought me as their guest, and everyone raises their hand.

But I’ve never been to any of their hometowns, and they barely know Houston from Dallas. Cara is a staunch Seattleite. Emma speaks with all the moxie and ebullience of her Jewish, Jersey roots. Adam grew up in same the small town in northern New York that once hosted the Woodstock music festival.

We eventually recognize each other’s friends as recurring characters in the stories we tell about back home. Sometimes, these friends even come to visit, and we can finally put faces to names. We exchange personal histories, made complete by chance encounters with the personalities of whom we speak.

Yet I still feel a psychological distance from my loved ones that leaves me unmoored and bereft. When virtual connection is but a crude imitation of the real thing, it often leaves me longing, as if to remind me that my faith in technology was always ill-placed. I can’t expect to exist online in the same fullness of person that my loved ones know of me, but I don’t have a better alternative.

When the pandemic first hit, we all learned that Zoom couldn’t hope to replicate what we’d lost, and when I’m quarantined in Paris, I can’t bring myself to walk around the city as my mom suggests. Staying at a safe distance, I know, would exacerbate my isolation.

I will spend many more days cooped up in the tiny apartment from which I once wanted nothing more than to escape. It becomes my safe haven, like a lighthouse when the waves of the Seine seem to be rising up to my toes, threatening to take me under. Paris is overwhelming in a way that I intuitively understood before arriving, but there are few feelings more paralyzing than having the City of Light at your fingertips and not having anyone with whom to share it. I’ll sit with this feeling of shame tight in my chest and resist the urge to call my mom. Fine. Yes. I’m lonely. But I’m lonely in Paris, and that is an improvement I would be foolish to take for granted, after a lifetime yearning to be anywhere but here. So I will act, when I feel like I cannot.

The digital approximates reality—coming close, but only going so far. Now that I’m home, I use a picture of The Abbey Bookshop as my phone background. I print out pictures to cover the wall of my room in Austin. I scroll through photo albums with a kind of masochistic wonder.

I was there, and now I am here.

I am here and want to be there.

Originally published in Spark Magazine, issue no. 19, Dec. 2022. Read the full issue here.