Plot Twist

I read the dragon smut book so that you don't have to ... but I think maybe you should.

My main hobby is reading, and I usually keep track of my reviews on Goodreads—my favorite social media platform in spite of a UX design that’s stuck in the early aughts. But sometimes, a book grabs me and won’t let go until I’ve articulated a couple thousand words or a deep discussion with a friend about it. I’m going to bring my longer reviews to Artichoke Heart, and I hope we can all discuss. Let me know if there’s a book you’d like me to cover next.

I take just as much pleasure in highbrow culture as in the lowest of the lowbrow. In fact, I try to not knock anything until I’ve tried it, with some key exceptions (anything Gwyneth Paltrow is peddling at goop, for example). This means that if a sexy “romantasy” book is going viral on TikTok and selling out at bookstores around the world, I’m going to have to read it.

Fourth Wing by Rebecca Yarros is set in Navarre, a fantastical country whose military officers are trained to ride on dragons and wield the magic that ensues from the dragon-rider connection. To reach the elite rank of rider, candidates must survive a series of deadly obstacles to their education at Basgiath War College, from the entrance ritual of crossing a narrow stone parapet onto the campus, to a life-or-death evaluation by the dragons themselves, fickle gatekeepers of who is worthy of becoming a rider. The dragons bond with the cadets on a metaphysical level, unleashing the aforementioned magical powers but risking the death of either partner due to the extreme depth of their connection.

Navarre has been at war with the neighboring kingdom of Poromiel (which rides gryphons instead of dragons) for centuries and weathered a civil war only a generation back. Commanding General Lilith Sorrengail was at the forefront of the effort to suppress the rebellion. Her 20-year-old daughter, Violet, is the main character of the book. Despite Violet’s chronic illness (a loosely veiled self-insert for Yarros’ own Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) and lifetime of preparation to become an academic within the Scribe Quadrant, her mother demands she uphold her older siblings’ reputations and enter the Riders Quadrant.

But third-year Xaden Riorson, whose father led the rebellion and was executed under Violet’s mom’s supervision, seems out to get Violet, and murder is well within the college’s rules of conduct. He’s also at odds with Violet’s childhood best friend and closest ally at school, second-year Dain Aetos. Can Violet survive their wrath—and that of the dragons and fellow students to whom she must prove herself?

If you’re not hooked yet … I honestly don’t blame you. I’ve never been a huge fantasy reader myself. I’m also not recommending this book as a work of high literature. The writing is firmly situated at the young-adult (YA) level, despite some of the spicier scenes. There is enough melodrama and convoluted syntax to justify legitimate outrage. But I also believe in the beauty of an escapist read, one that lets you lower your standards just a little but not abandon them completely (see also, anything by Emily Henry).

Despite its flaws, my theory is that this book owes its popularity to the generation raised by Harry Potter, Divergent, The Hunger Games, and an entire genre of dystopian YA novels—only now everyone is old enough to drive market trends and have sex. Several plot points in Fourth Wing track exactly to elements from the books of my adolescence. There’s a Draco character who is a thorn in Violet’s side and a Gale-type rival love interest from her childhood. The final moment of the book shares a similar tone with the end of Catching Fire (no spoilers).

But for all my familiarity with these conventions, I found myself genuinely surprised by several of the twists, including the climactic reveal. Sure, some of the smaller episodes were more predictable. In fact, a distinguishing feature of modern romance marketing is leading with the tropes a book includes, leaning into its formulaic nature. Perhaps my awareness of the industry speak sullied my reading experience, but sometimes I could see too clearly the architecture of the storytelling, as if Yarros might have worked backwards from pulling “slowburn,” “enemies to lovers,” “he fell first,” “forbidden love,” “forced proximity,” “love triangle,” and “opposites attract” out of a hat.

That’s what makes me so curious about this book. I’m finding it difficult to articulate a defense without undercutting myself—and I got an overwhelming sense from the prose that even the author would be hard-pressed to explain her breakout success. Yarros had written 19 books in various genres before Fourth Wing, a not insignificant number. Moreover, she’s a military spouse with six children who thanked her “Heavenly Father” first in the acknowledgements. That wasn’t the profile I’d expected to discover upon finishing the book—staying up until 2 a.m. two nights in a row to get through all 500 pages of it—though I guess I should have known better than to assume anything after romance author Colleen Hoover’s humble beginnings in East Texas led to a near-monopoly on the New York Times’ bestseller list.

In another anomaly for the publishing world, Fourth Wing only came out in April, but the second book in the planned five-book series, Iron Flame, will hit the shelves this November. That timeline is unbelievable; Harry Potter fans had to wait up to three years between books. I hope she can pull off a second wild success, but there are several signs beyond this fast-tracked publication schedule that make me worry she doesn’t have a sustainable skill. In a baffling choice, for example, the last chapter of the book switches perspectives away from the only narrator we’d known to that point. That betrays an insecurity, not a control of craft.

But I can’t analyze away the visceral reaction I had as a reader. Maybe I didn’t realize how much I’d missed fantasy world-building after years of reading mostly memoirs and literary fiction. Maybe the vivid language was doubly heightened by my lack of sleep. I laughed; I almost cried; I gasped and winced and at several points literally slapped a hand over my mouth in surprise. And yes, the sex scenes were—ahem—not of the young-adult variety. I wasn’t allowed to read The Hunger Games when it first came out because it was too violent, so I can barely believe that teenagers are reading this book.

Officially, this belongs in an emerging genre called “new adult,” featuring protagonists who are approximately 18-25 years old. As in Fourth Wing, the plot points and writing style might be closer to YA, but there is likely more mature content and at least some literary merit as well. Casey McQuiston’s Red, White & Royal Blue is a good example of this, and I was similarly shocked by how much I loved that book. I read it in one sitting, and the last chapter (set in Austin!) had me sobbing. Detractors have sometimes called the genre “smutty YA”—but there is inarguable emotional resonance in reading about characters at a similar stage of life, whether in that rocky territory of one’s early 20s or, famously, the teenage years of young-adult lit.

Fourth Wing isn’t the only sign of a nostalgia for the dystopias of the 2010s. The movie adaptation of The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, Suzanne Collins’ prequel to The Hunger Games, is set to release next month after three years of anticipation. (I read that book, too, and it was easily one of the worst books I’ve ever read.) The Cursed Child, the sequel to the Harry Potter series, also met with much fan disappointment upon its release in script form, though it would go on to have award-winning runs on Broadway and the West End. The 100, a television show based on the YA series, started airing on The CW in 2014 but fizzled to a mediocre final season in 2020.

Nonetheless, we keep trying to capture that dance between innocence and cynicism that once enchanted us about the genre: the idea that the adults might not have it all figured out, might actually be making the world worse for everyone around them and refusing to take responsibility for it, and only a disenfranchised underdog has the unique ability to redeem it.

It’s easy to see why this narrative is empowering for teenagers—especially those who came of age in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, the internet boom, and, later, the 2008 housing crash. For many of us, America was at war from the time we were in diapers until we could legally drink.

That’s not dissimilar to Navarre’s endless conflict with Poromiel. Basgiath War College could be seen as an analog for the military-industrial complex, both callously sacrificing young people to the maws of misguided foreign policy. Even The CW confronted the climate crisis and nuclear apocalypse head on with The 100, imagining a human race forced into space after making Earth uninhabitable.

This goes back to a conversation I have often with my friend Mary Shannon, about how sci-fi has always been an intellectual exercise as much as entertainment. From the 1920 Czech play R.U.R. giving us the word “robot,” to the plots of Fahrenheit 451 and The Handmaid’s Tale playing out in news headlines, speculative fiction has proven to be an important tool for social critique and political change. And what is progressive policymaking if not an act of radical imagination?

In Yarros’ world, characters are nonbinary, sex-positive, have chronic illnesses. This is a far cry from J. K. Rowling’s obstinate transphobia; “Cho Chang,” the name of her only East Asian character; and the goblins with hooked noses who control the Wizarding World’s financial sector. So maybe it’s not an altogether bad thing that as our imaginations progress—and so many existential questions in our society remain unsolved—that the genre continues to captivate and challenge us.

I await the rest of the series and its inevitable journey to the silver screen with unabashed anticipation—horny dragons and all.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

“I will cut adrift—I will sit on pavements and drink coffee—I will dream; I will take my mind out of its iron cage and let it swim—this fine October.” —Virginia Woolf

“A novel worth reading is an education of the heart. It enlarges your sense of human possibility, of what human nature is, of what happens in the world. It’s a creator of inwardness.” —Susan Sontag, The Paris Review, issue no. 137

I Miss You Already + I Haven’t Left Yet

I was supposed to see Del Water Gap play an ACL afterparty this weekend, so I’d been listening to his music on repeat. Milo’s recovery from a routine surgery did not go according to plan (he’s okay, just stubborn like his mama), so I ended up having to stay home with him.

The new album is wonderful regardless. Most of my favorites were already released as singles—“Coping on Unemployment,” “Quilt of Steam,” “All We Ever Do Is Talk”—but I also love “Gone in Seconds” and “Glitter & Honey.”

Pedialyte popsicles

After working a particularly grueling work event last week, one of my coworkers put me onto the brilliance of Pedialyte popsicles, available at Target and drugstores near you (not an ad).

Trader Joe’s Non-Dairy Pumpkin Oat Beverage

’Tis the season, when TJ’s becomes overrun with pumpkin-flavored frivolities. But I was finally able to open my windows over the weekend because the air was cooler outside of my apartment than in it, so I think we earned a little celebration of surviving this year’s record-breaking Texas heat. I could cry with relief.

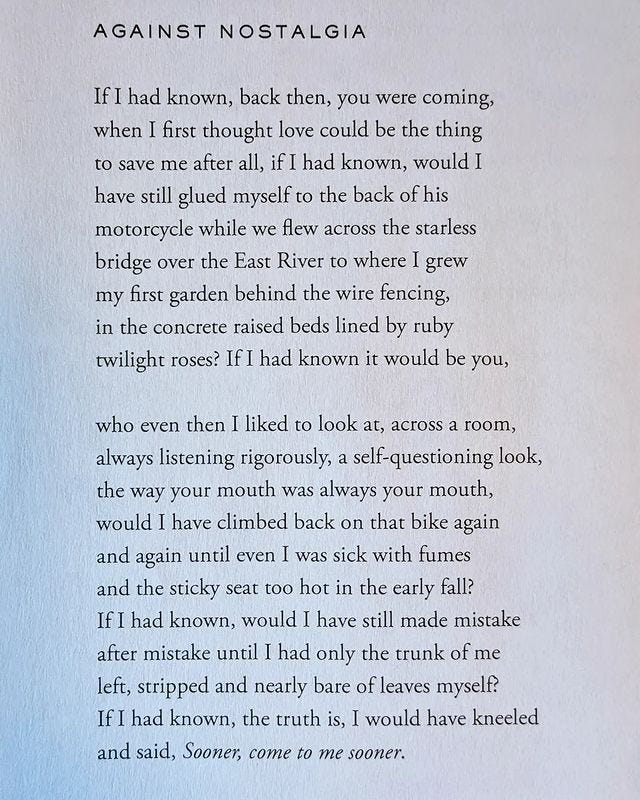

“Against Nostalgia” by Ada Limón

Limón was recently recognized in this year’s class of MacArthur Fellows, also known as the “genius grants.” This poem just about broke me when it came across my feed, and the account @poetryisnotaluxury is an altogether great follow.

Monsters by Claire Dederer

I’m realizing that my favorite thing to read right now is philosophical investigation combining autobiography and collective biography. (I raved about The Baby on the Fire Escape in my first newsletter before I even finished reading it, and it turned out to be one of my favorite reads of the year and maybe, like, of all time.) There’s a chapter on J. K. Rowling that expands upon my mention of her in this essay, and as someone who has a tattoo of a drawing by Picasso, the literal poster child (pictured on the cover below) for genius dirtbags, I have a vested interest in the question of whether we can separate the art from the artist.

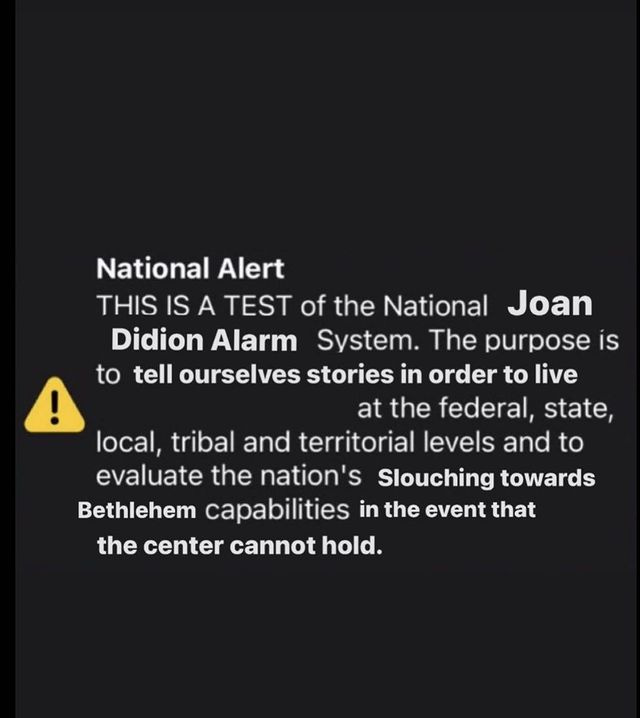

A meme for your Monday morning

The fact that this is a StraightioLab tweet reposted by Joan Didion’s literal nephew adds so many layers of hilarity.